- Undergraduate

- Foreign Study

- Resources & Opportunities

- Alumni

- News & Events

- People

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

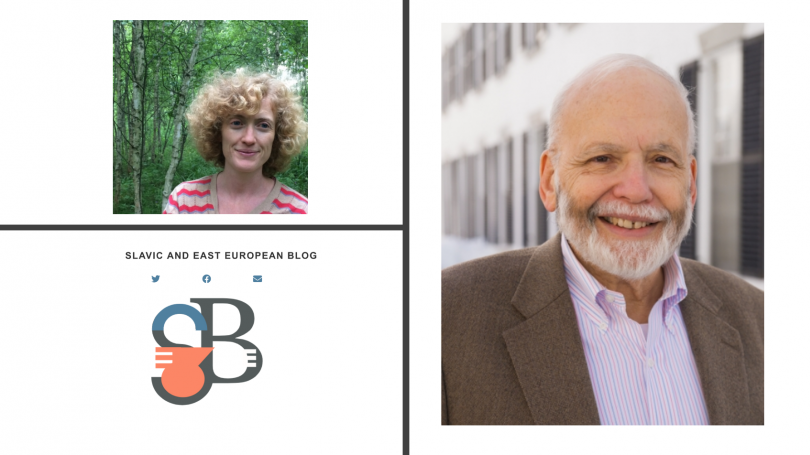

Assistant Professor Ainsley Morse interviewed Professor Emeritus Barry Scherr recently in conjunction with Slavic and East European Journal to create an archive of the history of our field and discusses his career as a Russianist.

Ainsley Morse (AM): So the first question is about your own education—what was it like—it says "pros and cons," so, what worked and what was not so great.

Barry Scherr (BS): OK, so my education in Russian-related matters—Slavic-related matters—started at Harvard, then at University of Chicago for graduate school. For me one of the weird things is, when I went to college, I actually managed to enter as a sophomore—you could do that by taking advanced-placement courses—and that was geared toward those people who knew exactly what they wanted to do and had great preparation. I had neither, so it was really..

AM: You just had the credits.

BS: The credits. So it was probably a mistake on my part—during my first year I think I declared maybe 4 or 5 different majors, I hadn't the foggiest idea what I wanted to do.

AM: Was Russian one of them?

BS: No, it wasn't at the time, that was part of it too. I took Russian because I had thought I'd probably end up majoring in one of the hard sciences, and in those days the hard sciences required languages for PhDs. You actually needed two languages. I was told that particularly if you do chemistry or physics or math, Russian and German were probably the two. I opted for Russian, took a year of Russian, finished the year and—I really don't even remember what I was majoring in then (maybe philosophy and math together, I went through lots)—anyway, I wasn't really happy with anything at that point. Then somehow over the summer a couple of things happened to me. One of them is I was told that they had an intensive second year at Harvard, which people loved—they said the regular second year course was a bit blah—I figured it'd be great to take that.

AM: Oh yes, I taught it!

BS: So anyway, I was strongly thinking of doing that, but I was still going to major in something else, figured the intensive course wouldn't get in the way. In the spring I had taken a comp lit course, which I didn't like particularly except for Anna Karenina, and I was thinking I'd liked some Russian literature I'd read before, I'd had a year of Russian, I'm probably not going into the hard sciences, so why don't I do Russian. See, I was already a junior, and that was one of the problems, my junior and senior years were both largely Russian, though not totally—I really rushed into stuff.

AM: Who was teaching Russian at the time? Was it taught by the full professors, or did they have the preceptor system?

BS: Oh, the language? Yeah, I don't think they were called preceptors then. Mostly instructors, graduate student instructors. Bob Rothstein, who went on to a long career at UMass-Amherst, was one of my—he was my teacher for the intensive second year, actually. He was a grad student at the time. In fact, the ones I came in contact with were pretty much all grad students, until you got to third-year Russian.

AM: And were there any Russians around? I guess Jakobson was around?

BS: Oh, Jakobson, yes. The Russians were at the regular tenure-track professor level, tenured level actually. It was primarily an émigré department, though Horace Lunt was chairing it, a great linguist, probably the only person in those years who could actually go up through the ranks and become a professor— they'd hire people for several years and push them out, that was the norm at the time. But if you look back at it, there were some great names there—Setchkarev, whom I had for Slavic 150, the introduction to Russian literature, and also the Pushkin course. Years later, I went on to do all this work with Russian metrics and versification, and Taranovsky was there teaching back then… But in those days almost no undergraduate dared take a course with him, and given the fact that I had started Russian so late I would never have been ready for his classes at the time. But he was there.. And Albert Lord, doing the South Slavic stuff… they were really famous people. And I audited a course from Roman Jakobson; he was certainly there, very much a presence.

AM: How many Russian majors were there at the time?

BS: A handful, I mean, several, you know, 4-5-6 at most in a given class, it wasn't huge. But you had all the graduate students around, there was a lot of interest in Russian—it was still the post-Sputnik years, I got there in '63 as an undergraduate, so interest in Russian was still fairly strong. And you had a lot of, you know, at Harvard they still have that History & Literature major, don't they? [AM: Yes] So a lot of students were doing that, you really had a lot of people around doing Russian, you didn't feel like it was that tiny an area necessarily, except for the small handful of majors. I remember, I was impressed when I took a junior seminar with Andrew Field; he had already published his translation of Sologub's Melkii bes, and here he was still a grad student, hadn't taken his qualifying exams yet… So, it was really quite a place in a lot of ways, a little intimidating, but good.

For the full interview please go to the following link in Slavic and East European Journal.